- Home

- Max Besora

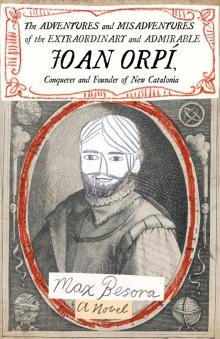

The Adventures and Misadventures of the Extraordinary and Admirable Joan Orpí, Conquistador and Founder of New Catalonia

The Adventures and Misadventures of the Extraordinary and Admirable Joan Orpí, Conquistador and Founder of New Catalonia Read online

Praise for Max Besora

“Flagrant, shameless, high-voltage, and sometimes just consummately silly. I can’t think of another translator who could have pulled this off, but like any great writer who feels they have total license to do whatever the hell they want with their language, Lethem creates what the narrator describes as ‘a language that constitutes the topography of its own world’, not striving for an accurate period reconstruction, but an archaism that’s invented, anachronistic, bastardised, defiantly inconsistent and totally, gloriously fun.”

—Daniel Hahn

“An heir to Rabelais, Cervantes, Sterne, and Swift, Besora has conceived his novel as a giant neo-baroque container with room for everything and more besides. The combination of events, registers, genres, and characters is manic in its variety.”

—Pere Antoni Pons, Ara

“Like Don Quixote, this is a chivalric novel, seasoned with the humor of an author with wit in spades. Besora grew up with the toxic style of the great US underground cartoonists, the ‘Weirdo’ gang, and you can tell.”

—Time Out

“This novel is here to atone for a glaring oversight in the history of Catalan literature, reviving a tradition that has seemed all but dead since the time of Tirant lo Blanc, since any language deserves, at the very least, two great satirical novels; and this one is so Catalan it hurts.”

—Montserrat Serra, Vila Web

Copyright © 2017 by Max Besora

Translation copyright © 2021 by Mara Faye Lethem

First edition, 2021

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: Available.

ISBN-13: 978-1-948830-24-9 / ISBN-10: 1-948830-24-8

This project is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts and the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature.

The translation of this work has been supported by the Institut Ramon Llull.

Printed on acid-free paper in the United States of America.

Cover Design by Tree Abraham

Interior Design by Anthony Blake

Open Letter is the University of Rochester’s nonprofit, literary translation press: Dewey Hall 1-219, Box 278968, Rochester, NY 14627

www.openletterbooks.org

The ADVENTURES and MISADVENTURES

of the EXTRAORDINART and ADMIRABLE

JOAN ORPÍ,

Conquistador and Founder of New Catalonia

CONTENTS

Preamble

Book One

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter IX

Chapter X

Chapter XI

Chapter XII

Chapter XIII

Chapter XIV

Chapter XV

Chapter XVI

Chapter XVII

Chapter XVIII

Chapter XIX

Book Two

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter IX

Chapter X

Chapter XI

Chapter XII

Chapter XIII

Chapter XIV

Chapter XV

Chapter XVI

Book Three

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter IX

Chapter X

Chapter XI

Chapter XII

Chapter XII

Chapter XIII

Chapter XIV

Chapter XV

Chapter XVI

Chapter XVII

Chapter XVIII

Chapter XIX

Chapter XX

Chapter XXI

Chapter XXII

Chapter XXIII

Chapter XXIV

Chapter XXV

Chapter XXVI

Chapter XXVII

Chapter XXVIII

Preamble

Everything we know about the figure of Joan Orpí del Pou (Piera, 1593–New Barcelona, 1645), founder of our country, we know thanks to the historian and geographer Pau Vila, who states, in his rigorous, severe biography—the only one to date—that Orpí was “a Catalan man who went through a lot and managed to come through it all.”1 However, that study was the last of any research into this personage—a Catalan lawyer who worked for the Spanish Crown, became a conquistador and, finally, founded New Catalonia on the other side of the world—as the Chronicles of the Indies and modern historiography have, generally, shrouded him in silence.

About a year ago, however, destiny or providence brought to my hands an unpublished volume that shed further light on our character’s story. It was while I was in the Archives of the Indies in Seville researching some relaciones de servicio2 from the conquest, when a sheaf of old papers tied together with a goatskin cord fell to the floor. The text had a printed cover but the pages inside were written in a shaky hand faded by the passage of time. The poorly cut and glued paper and the lack of stains made it clear that it was an unpublished document. After a few months of furious literary archeology, during which time I deciphered and copied the text, I came to find some wholly surprising results. The book was written by an anonymous soldier who, during the 1714 Siege of Barcelona, had transcribed his captain’s oral narration of the life and adventures of a man named Joan Orpí, who had lived in the century prior. The manuscript was not published or distributed in its time, nor in the centuries that followed, remaining forgotten in that dusty corner of the archives, until I “stole” it in order to make its contents known to both the scientific and lay communities.

Now, would it be accurate to call those soldiers from 1714 “historians”? The answer is uncertain. In fact, it’s more than likely that this document is as dubious—if not more so—as the Ossianic poems, the Fragmentum Petronii, or Scheurmann’s Der Papalagi, and we have made that clear in this critical edition, in which the dates do not always match up with the accepted timeline. It is precisely in such manuscripts as ours, which is to say deriving from an oral source, that such historiographical problems often crop up. How much truth is there in this document? To what extent does literature reflect society and to what extent does history? How does literature transform our perception of history? These questions, while perfectly legitimate, open up a whole can of worms, since any close inspection of history books soon reveals divergences. The Adventures and Misadventures of Joan Orpí blurs the distinction between poiesis and mimesis (or what boils down to the same thing: invention versus history, because they are but two faces of a single coin), and employs an extraordinary variety of narrative strategies including the picaresque, rumors, decrees of the period, annotations, chronicles, legends, official government papers and files, myths, letters, fables, songs, contradictory narratives ranging from popular to elitist, hegemonic and counterhegemonic, with trips down to various hells, legal treatises, the Byzantine or chivalric nove

l3, records, polemic tracts, catechisms and sermons, the rhetoric of the heroic epic, biography, allegory, satire, and, of course, the historical events of the conquest of America that later would become legendary in the conquistadors’ own words, in The Chronicles of the Indies.

In short, this text offers a wide range of narrative resources that fill in the blanks left by Pau Vila’s biography, and show Joan Orpí moving between two very different times: Catalonia on the Iberian peninsula and New Catalonia on the American continent; modern Europe and “primitive” America; the Baroque world and the incipient Enlightenment; the mechanistic and the magical views of the world; always between two spaces, constantly fluctuating between the real and the imagined. This ambiguity allows us to use this historical personage as an instrument for reinterpreting the subject in history, for rethinking the relationship between the colonizer and the colonized, as well as the figure of a person made metaphor who must face up to the failure of a utopia and accept Sic transit gloria mundi, a person who created an alternative historical reality.

To conclude this introductory note, we want to point out that we decided to revise the manuscript, transporting the narrator’s voice to modern Neo-Catalan and leaving only the dialogue in the original language, to avoid losing contemporary readers’ interest. That said, we have kept the changes and annotations to an absolute minimum, except for the footnotes (which meet the criteria for the quality and precision demanded by the Academy) used to correct some historiographical errors or simply insert information to allow modern readers to judge for themselves.

Walter Colloni

Professor of Neo-Catalan Postcolonial Studies

Universitat de Sant Jeremies

New Catalonia

4

___________

1. See Joan Orpí, l’home de la Nova Catalunya (Ariel, Barcelona, 1967) and the later edition, expanded and translated into Spanish by Pau Vila himself: Gestas de Juan Orpín, en su fundación de Barcelona y defensa de Oriente (Universidad Central de Venezuela, Venezuela, 1975).

2. i.e. Reports delivered to the Spanish Crown in order to obtain recognition for successful missions and compensation in the form of pensions and other rewards from the royal authorities.

3. The subtle distinction between fantasy and reality, on which the power of conviction of many chivalric novels lies, was due to the audience’s demand for guaranteed true events. Often, in their prologues, they claimed to be adaptations of some original document or a manuscript happened upon by chance.

4. i.e. The original cover to the manuscript. The printing house of Sebastià Comelles was famous in its day for publishing the works of Lope de Vega and Avellaneda’s apocryphal third volume of Don Quixote. However, neither the font size of this manuscript’s title nor the metal type match with the Barcelona printer’s typical style. Not to mention that the rest of the text is written out by hand. As such, we’ve deduced that this cover is merely an intellectual forgery, as I explain in further detail in an essay entitled “Joan Orpí: History or Literature?” (Edicions La Parranda, 2097).

Dicere etiam solebat nullum esse librum tam

malum ut non aliqua parte prodesset

Gaius Plinius Secundus, Epistulae, III, v. 10

The ADVENTURES and MISADVENTURES

of the EXTRAORDINARY and ADMIRABLE

JOAN ORPÍ,

Conquistador and Founder of New Catalonia

September 10, 1714,

The Siege of Barcelona

A group of infantry soldiers and their captain opt to smoke and drink in an abandoned theater rather than be stationed at the walls, firing against the Bourbon troops. Bombs fall on the city night and day, ceaselessly. Everything is ruin and desolation. Death hangs gloomily over everyone, scythe at the ready.

“What mindless suicide!” one of the soldiers suddenly exclaims. “We shall die as rats yf we continue on this way. A pox upon the Hapsburgs and a pox upon the Bourbons: Ni dieu ni maître!”

“Die as dogs, jolt-head!” chides another soldier. “I should beat thee down at present! For at least we shall make history! They’ll write book after book about us, they will erect museums, make paintings, write poems in our honor … we shall be heroes of the fatherland!”

“Aye, if there’s any fatherland left,” grumbles a third infantryman.

“I had rather be a living deserter than a dead patriot,” muses a fourth soldier.

“That’s enough! Quiet, all ye!” bellows the troop’s captain. “Chance to die and chance to live but, in any case, remember that the fatherland doesn’t always coincide with the territory. I wot the tale of a man named Joan Orpí, who refounded our Catalonia on the other side of the globe, less than a century hence. On my word.”

“Incredible!”

“Cock and pie!”

“And what befell henceforward, Captain?”

“And what befell henceforward, bid ye? Well, in ’is quest to try that all, he lived a thousand and one adventures,” declares the captain. “Ye shant find these in any book of history, yet they be no less memorable or less important. Au contraire. Would ye care to hark, and forbear complaining for a time?”

The infantry soldiers smile like children, nod their heads, and perk up their ears. They pour more wine and pass around tobacco. The captain/narratorlights his wooden pipe and begins his declamation.

“Who was this adventurer what founded a New Catalonia thousands of leagues away, yet went to the diet of worms leaving naught a trace in our history?”

“Joan Orpí!” one soldier shrieks.

“Precisely! Who traversed seas fill’d withe mythical monsters and virgin forests at risk to his life (and the lives of many others) for a fistful of gold coins and (perchance) posthumous glory … ?”

“Orpí … !” bellows a soldier.

“The selfsame! And who risk’d chicaning the very Catholic Kings and came cross’t near as many enemyes as friends?”

“Christopher Columbus … ?” ventures another soldier.

“No, ya beef-head, none other than Joan Orpí! At least that was what I was told by a corky criollo from the Yndies I happen’d upon one night when tippling in Seville. He quoth to be a ‘friend of a Catalan conquistador, humble altho an old Christian5 and a nobleman of New Andalusia in the Americas, later founder of New Catalonia.’ Thus he even spake Catalan.”

“Hold up … one moment, Captain!” says one of the soldiers. “Canst thou truly trust a brandy-face? Art thou convinsced the criollo was whom he sayd to be and that he werent lying with a latchet? How many years pass’d betwixt these events and the telling of them? And, once for all, why have I this tic in mine eye each tyme I get nervous?”

“Enuf tilly-tally, soldier, and merely heed the tale,” orders the captain, in a didactic tone. “Whence my ‘informant’ explaint this historical drama to me, the criollo in question were four sheets to the wind. Nonetheless, I didst believe him. And knowth ye why? 1) For the criollo spake Catalan, and 2) for I be a man of faith (faith in the imagination, to be clear!). And now, allow me begin with Chapter XVI, of whych I am inordinately fond.”

___________

5. i.e. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the subject of blood purity divided the Hispanic world into new Christians, in other words, those descended from Arabs or Jews, and old Christians, of pure Christian blood.

Chapter XVI

In which young Orpí celebrates Carnaval with his fraternity and ends up dressed as the Stag King

I shall begin with a day when Joan Orpí was celebrating Carnaval. Following the parade, our young hero ended up in a cemetery, where a band of joyous revelers were engaged in a wide range of obscenities. Some were licking others’ anuses, some were eating fruits and tomatoes they’d rubbed on their genitals, and others were drinking sacramental wine and masturbating and dancing to the improvised music of drums and tambourines. All were dedicated to the collective ritual, singing, shrieking, praying, making offerings and insinuations, muddy and half nude … ducks and rab

bits fell at their hands … hens were violated and eviscerated … some slathered themselves with the blood of the dead animals—

[One instant, Captain … halt! Forbear the tale!]

“How now?” he asks, irritated.

“For the lyfe of us, we cannot fathom why thou beginnst with Chapter sixteen. Would logick not state the first Chapter?” asks one of the soldiers.

“Yea, start withe the first! The first!” cry out other soldiers.

“How’s that? Doth ye seek the typical story with a beginning, middle, and end?” asks the captain, perplexed. “Dunderheads! Don’t ye know that true literature is only true when written against itself? Why put plot over language and form?”

“Here we hie again,” complains one of the soldiers. “Art thou one of those pedantic academics, ay? For if that be the case, I prefer to be killt by enemy troops …”

“Numbskulls!” bellows the infuriated captain. “When I speak of going against the narration I don’t mean there shall bee no story, no adventures, no characters! I speak of the need for a hybrid construction, plurilingualism, exaggeration, hyperbole, pastiche, and bivocal discourse to bring together what convention & morality strive to keep separate. Literature must be a frontal attack designed to suspend all rational judgment in order to reinvent it each second anew!”

“I cannot bear these sermons …” says one of the soldiers.

“If he keeps up this proselytizing, I’m outta hither …”

“Yawn …”

“Fine!” exclaims the captain in exasperation. “Okay, Okay, fine! Quit thine complaining! I shall beginne at the beginning, as you wish! But no more interruptions, I’ll lose the thread, and judge me not for mine invention, but rather for the grace of my wit, glossed in three books and their corresponding Chapters, which one of ye shall ‘copy’ anon. And that’s an order!”

Book One

In which is narrated, with great gusto and an eye on posterity, Orpí’s infancy and childhood, first in the town of Piera and anon during his studies in the city of Barcelona, where he had varied experiences, as many good as bad, which taught him that life is no bed of roses but rather a long ordeal where one learns from hard knocks, and as such and befitting his story shall be explained perhaps not exactly as it truly happened, but at least quite similarly.

The Adventures and Misadventures of the Extraordinary and Admirable Joan Orpí, Conquistador and Founder of New Catalonia

The Adventures and Misadventures of the Extraordinary and Admirable Joan Orpí, Conquistador and Founder of New Catalonia